Select your investor profile:

This content is only for the selected type of investor.

Individual investors?

Bond investors and the temptations of the Costanza rule

After a tough start to the year, should global bond investors emulate Seinfeld's George Costanza, and act against their instincts?

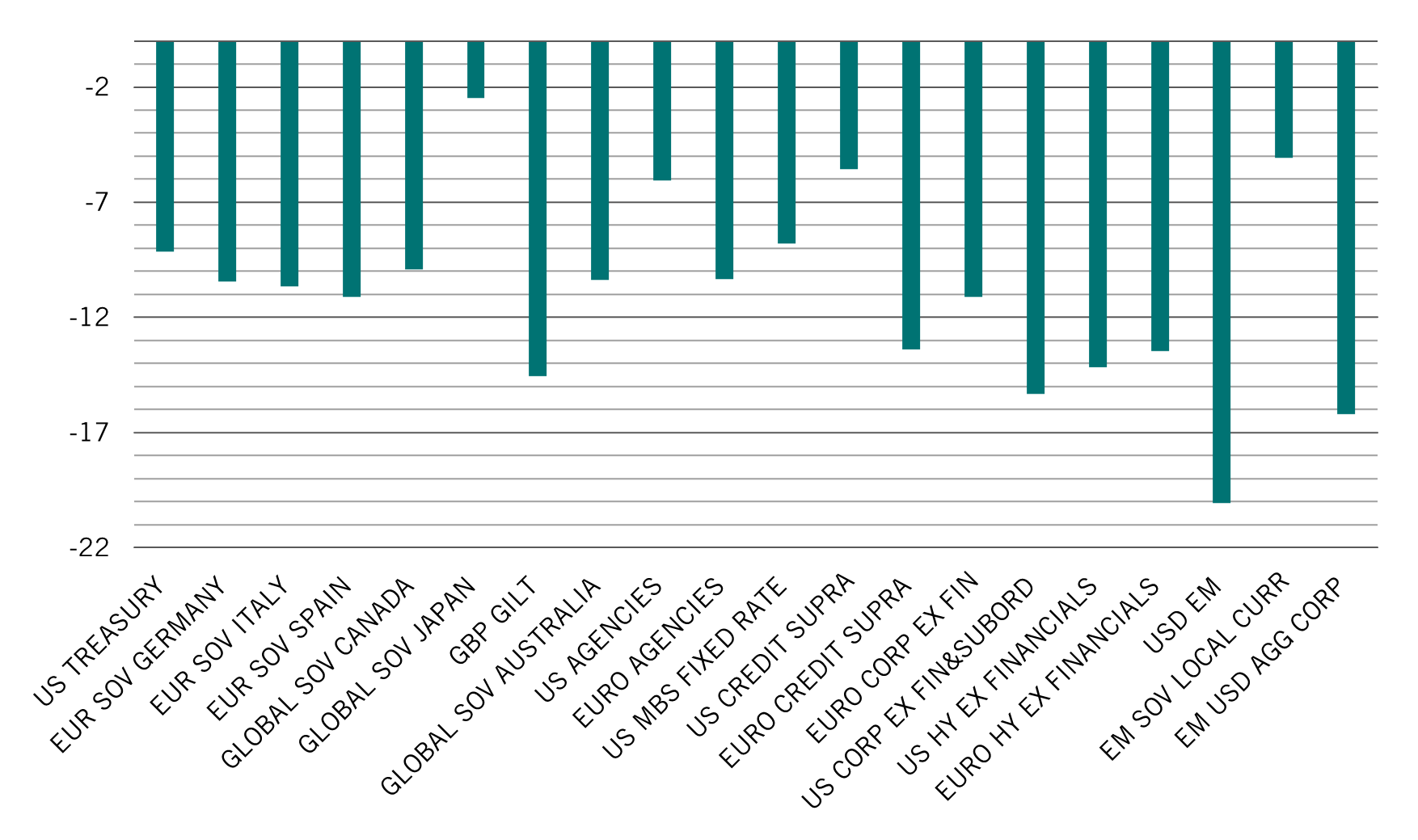

This has been an incredibly difficult few months for bond investors. There was no place to hide as most fixed income asset classes have fallen more or less in tandem (see Fig. 1).

It reminds me of an episode of the 1990’s US sitcom Seinfeld, in which one of the characters, George Costanza, remarks that every decision he has ever made has been wrong, and that his life is the exact opposite of what it should be. His friend Jerry Seinfeld convinces him that "if every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right". Costanza then goes to do the opposite of what he would traditionally, with amazing results.

I think Costanza reflects the feelings of many fixed income investors over the last six months: “if only we had done the opposite of what we usually do, if only we were short fixed income”. But, going forward, will doing the opposite, like Costanza did, guarantee future success? Do we believe that being short bonds is going to bear fruit now that yields are higher and spreads are wider?

It is abundantly clear that the instincts that have helped investors generate healthy returns since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) have not served them well in the last six months. Expecting central banks to continue to bail out financial markets in times of stress, for instance, has proved costly, as has the notion that longer duration bonds would serve as insurance against recession.

To resolve these conundrums, we first need to establish what we know. Pictet Asset Management’s Global Bond team has long believed that a wiser course for investors is to focus on the structural trends that influence interest rates, bond spreads and currencies rather than shorter-term cyclical ones.

We have identified three: rates low for long, the European crisis (as the region yo-yos between integration and fragmentation) and China’s transition (from export-led to domestic growth).

Rates low for long, really?

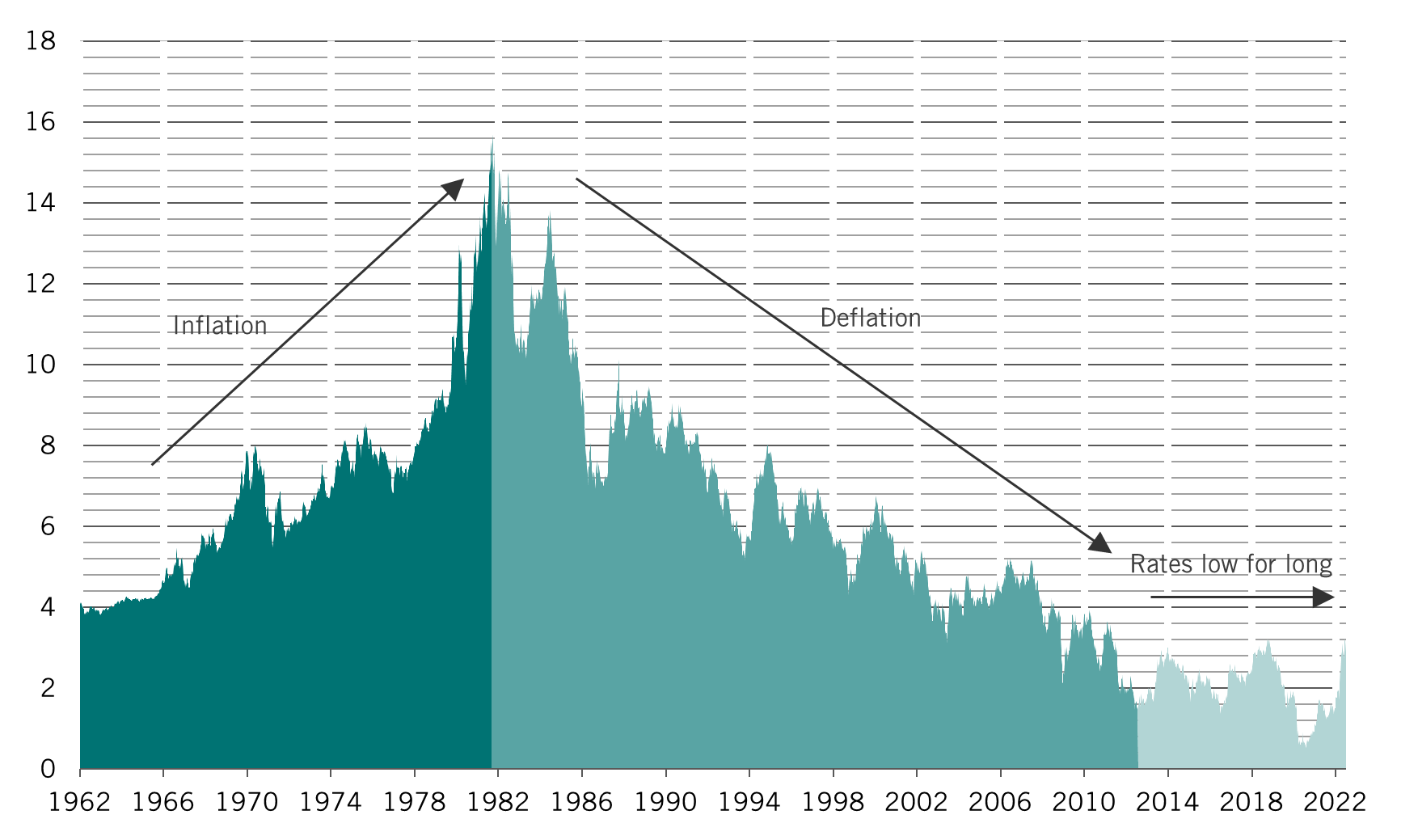

Of the three, “rates low for long” might appear to be the most difficult to rationalise. How can we still believe rates will remain low for long if inflation in most of the developed world has reached 8 per cent?

We originally embraced this idea in the belief that an ageing population, combined with increasing levels of debt, independent central banking and prudent fiscal policies, would make developed economies prone to disappointing growth and to disinflation. Add to that the “peace dividend” that came with the end of the Cold War, and the ever expanding rate of globalisation, and we had the perfect recipe for rates staying low for a pro-longed period of time.

Yet even before the pandemic there were problems with this thesis. Donald Trump’s presidency ended decades of prudent fiscal management in the US and the European crisis put the Maastricht criteria on hold. At the same time, the trade tensions between the US and China threatened globalisation. Now the war in Ukraine could spell the end of the peace dividend and send commodity prices to worrying levels.

Yet demographics trends have not changed and still point to lower economic growth over the long term. The growth in the working-age population has been in steady decline for at least a couple of decades in the developed world. Productivity growth has also been slowing (barring distortions for the pandemic). We believe the higher level of government debt will continue to weigh on productivity.

Paying back debt – instead of investing for growth - tends not to be very productive. The additional costs of onshoring and supply chain risk management in certain industries won’t help, either.

Therefore, the long-term trend continues to point to low real rates. The extent to which central banks can hike rates is limited by anaemic economic conditions in the developed world, aggravated by the war in Ukraine, as well as by the real estate crisis and Covid lockdowns in China.

The real unknown is inflation. Since the GFC, central banks have been battling with deflation, and before the pandemic, it seemed that they were losing that fight.

It was only when supply chains began falling apart due to Covid, and monetary and fiscal stimulus went into overdrive, that inflation began moving rapidly beyond central bank targets. The persistence of the inflationary surge took many analysts, economists and investors by surprise, ourselves included. By January 2022, it was clear that not only was inflation more entrenched than previously thought, but that it was spreading beyond food, energy and housing.

Where will inflation end in 2022 and 2023? It is anybody’s guess. Forecasts in Bloomberg’s survey for the US range from 4.9 to 9 per cent for 2022 and 2 to 5.2 per cent for 2023, with medians of 7.5 and 3.4 per cent, respectively. There is similarly broad range of forecasts for Europe. By contrast, between 2012 and 2020 US CPI inflation oscillated between 0 and 3 per cent and base rates between 0 and 2.5 per cent.

Our philosophy has always been not to depend too much on the prevailing macroeconomic forecasts. Instead, we want to balance our portfolio between high and persistent inflation and falling inflation.

At the same time, however, it is important to acknowledge that the way in which fixed income asset classes behave relative to one another has fundamentally changed.

Higher, more persistent inflation has reversed the correlation between government bonds and riskier assets. Put simply, higher inflation is now bad for riskier asset classes, while lower inflation is good.

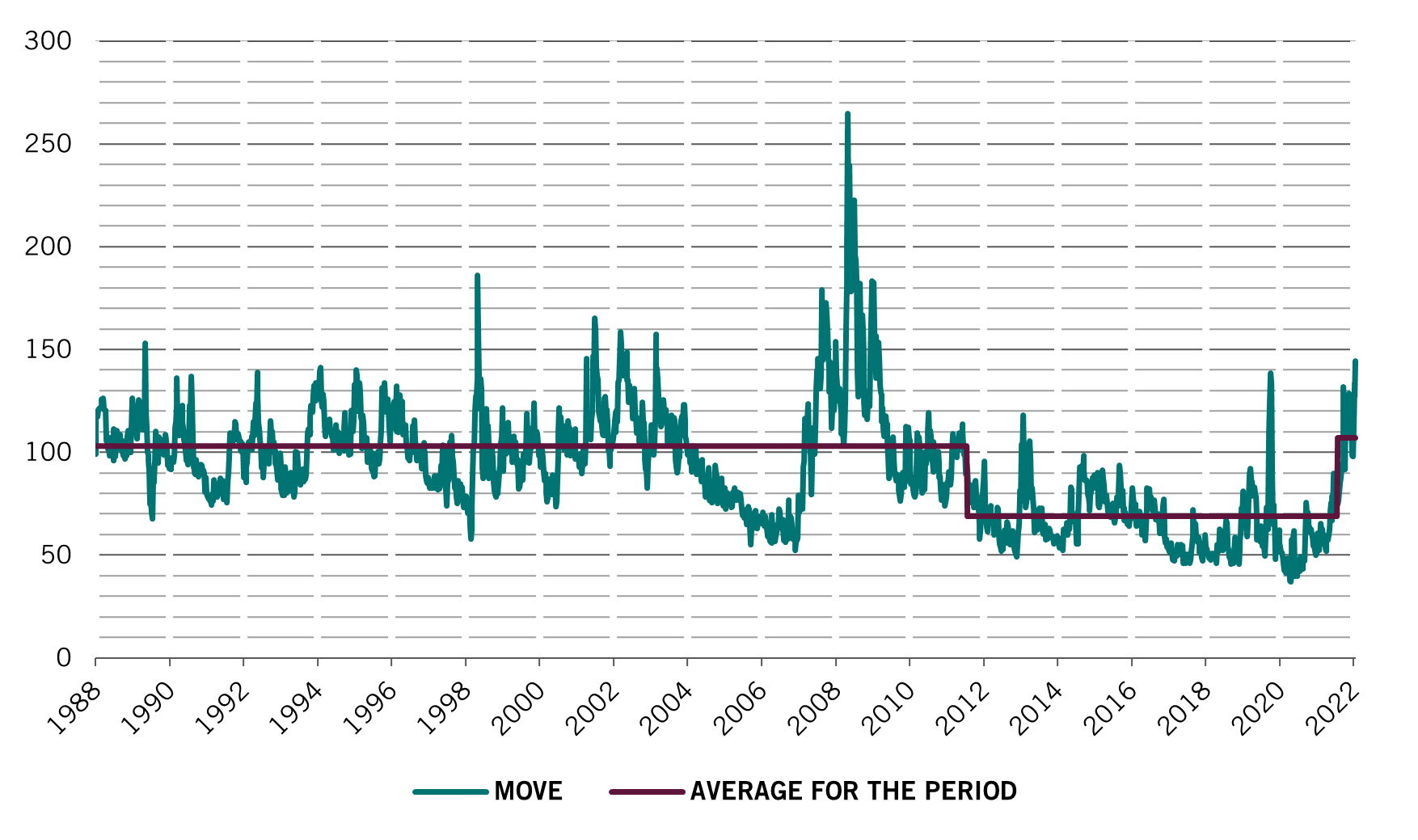

Volatility is also back with a vengeance, and not just because of the uncertainty about the global economy. Central banks are no longer suppressing volatility via quantitative easing or the infamous “Fed put” on equity markets.

We believe volatility is here to stay, and that central banks will be focused on controlling inflation. Politically, quantitative easing is becoming harder to justify as it appears to have exacerbated social inequality. As a result, we have reduced the risk in our portfolios – in both our government and corporate bond investments.

As long as inflation remains above central bank targets, correlations across fixed income assets are likely to remain high, as is market volatility.

Credibility at stake

For all this, there are considerable differences in the ways in which central banks are responding to such challenges.

The Bank of England, for example, seems to be very fearful of engineering a recession, while the ECB is concerned about the risk of fragmentation within the euro zone. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), meanwhile, is worried about the housing bubble. All three might be willing to take more risks in order to protect stability – and thus compromise their credibility in terms of fighting inflation.

The lessons from the 1970’s is that there are shortcomings to this kind of approach. The Fed, under the leadership of Arthur Burns, failed to contain inflation after the first oil shock in 1973. Inflation expectations soared, leaving Burns’s successor Paul Volcker no choice but to take drastic action when a second oil shock hit in 1979, which he hiked rates to 20 per cent. We believe that is why the US yield curve is so flat, whereas others are quite steep – markets believe that, without other priorities, the Fed will succeed in taming inflation more quickly, and rates will stabilise sooner. From a bondholder perspective, we prefer central banks that are credible in fighting inflation.

For the ECB all choices are difficult. Can it find a credible backstop to prevent the borrowing costs of the weaker and more indebted economies (such as Italy) from spiralling out of control, and, at the same time, be credible in fighting inflation at a time when the euro zone is facing a terms of trade shock due to the war?

Not a full "reverse Costanza"

Let’s come back to our friend George Costanza and whether we should now do the opposite to what we did in the decades before 2022. We used to express our “rates low for long” conviction by being overweight duration and long investment grade credit. Should we now be short rates and short credit? It depends on the attitude of the central banks.

If the central bank is credible, like in the US, we believe it is worth owning more of that country’s currency, more duration (or longer-dated bonds) and some high-quality investment grade credit.

If the central bank is not credible, we believe Costanza’s strategy should work: shorting the country’s currency, its bonds and its corporate debt. The problem with just reversing course at a time when markets are volatile is that volatility becomes the enemy of every strategy.

Trusting economic forecasts when the range of possible outcomes is very wide is also, in our view, too much of a gamble.

Our global bond portfolios had a difficult start to the year, due largely to the fact that all bond asset classes were falling in unison. We have responded by reducing risk and reassessing the strategy.

Now we believe it all boils down to inflation (uncertain) and central bank credibility where actions speak louder than words.

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.