Select your investor profile:

This content is only for the selected type of investor.

Individual investors?

The case for active investing in China just got stronger

In the current fluid regulatory environment, investing in Chinese shares calls for an active investment approach.

Investors are routinely reminded of China’s uniqueness. Mostly it has been by way of positive surprises – such as the economy’s dramatic rebound from the Covid-19 pandemic. But lately a series of shocks have made it painfully clear that Chinese assets aren’t suited to a passive buy-and-forget approach.

During recent months, Beijing has taken the markets by surprise from a number of directions. It has cracked down on the technology sector and on Chinese companies listed abroad. But it was when the government banned profits on the country’s private sector tutoring market – estimated to be worth some USD100 billion – that investors truly felt the significance of Beijing’s interventions. This was merely reinforced when it then outlined a five year plan for a strict new regulatory approach, particularly to tech companies.

More than anything this demonstrated the unique risks of investing in Chinese equities. Even the relatively safer domestic market for Chinese A-shares has been roiled by recent turbulence. That matters for investors in emerging market equities – even those who don’t have direct holdings of Chinese stocks. And it is particularly true for those invested in mainstream index funds, given China’s heavy weightings in major market benchmarks.

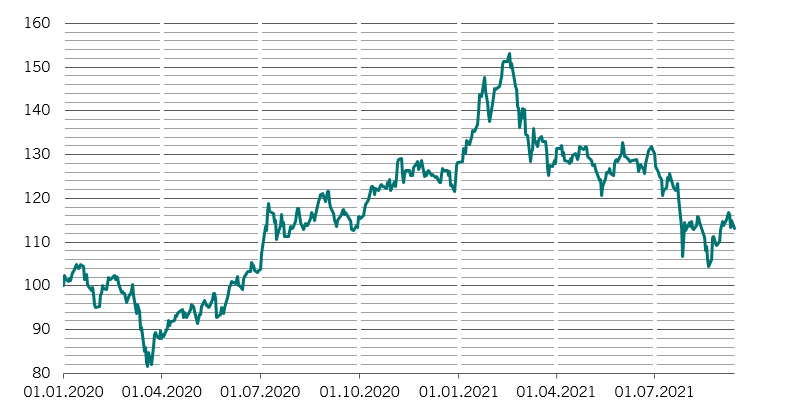

Shocks to the system

MSCI China total return index, USD. Rebased to 01.01.2020 = 100

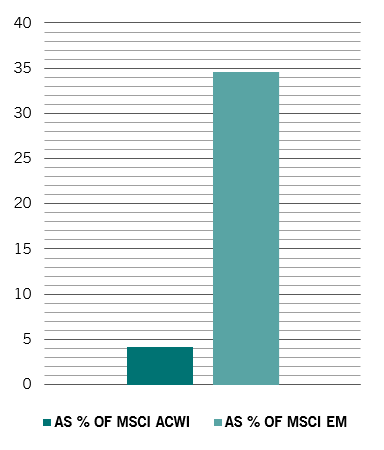

China's index footprint

Investors who hold Chinese stocks through allocations to mainstream emerging market indices have also suffered.

MSCI China market value as percentage of MSCI All Country World Index and MSCI EM Index

The size of the Chinese economy and the increasing maturity of its market makes it a behemoth in the emerging market universe. China’s stocks currently account for 35 per cent of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. And thanks to MSCI’s decision to start incorporating China’s domestically-listed equities, or A-shares, in its benchmarks from 2019, the country’s weighting in the index is set to increase.

China's growing heft – which is also testament to success of Stock Connect, an arrangement that allows foreign investors to trade Shanghai- and Shenzhen-listed securities on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange– could eventually allow the mainland Chinese market to rival Wall Street. But that comes with significant caveats.

Even if China’s domestically listed A-shares have been a relatively safer bet during the sell-off, with investments flows into A-shares remaining strong, risks are multiplying there too.2

Chinese challenges

Beijing’s regulatory interventions during the past year have highlighted some of the biggest risks facing investors. A proper understanding of China’s political weather is clearly important. Other factors may be less dramatic, but are also important for investors to consider.

The first is governance. The Chinese market has very different regulatory criteria for its companies compared to those in more developed markets. And so for active investors, the emphasis shifts to pursuing positive ESG practices when engaging with these firms. So while Chinese companies that are also listed in Hong Kong or New York – traded as H-shares or American Depository Receipts – have to meet strict governance rules, minority shareholders on the mainland have significantly weaker legal protection. Buying an index makes it impossible to separate out the bad from the good.

China may represent the future of investing, but it's a future strewn with potential potholes.

The third factor is macro-economic policy. Beijing did a stellar job of steering the economy out of its steep pandemic-driven decline – China was the first major economy to more than recover pre-pandemic levels across most dimensions. It was just as successful after the global financial crisis a decade ago. But for investors, the detail determines which assets benefit. Is the government focusing efforts on domestic demand or export industries? Is its primary mechanism non-financial credit creation or is it through state spending?

Lastly, routine trading suspensions continue to bedevil investors in A-shares. It’s relatively easy for mainland-listed companies to suspend trading in their shares, and for periods of as long as six months. Indeed, half of all A-share companies had suspended their shares in 2015 during a severe bout of stock market turbulence.3

The opening up of mainland China’s equity market to foreign investors offers huge potential. But buying them through passive, indexed products is a poor choice. Being locked into an index provider’s share weighting exposes investors to a number of risks. It makes them over-exposed to the most vulnerable sectors as the Chinese economy faces significant rebalancing. And it doesn’t allow them to factor in differing qualities of corporate governance. China may represent the future of investing, but it’s a future strewn with potential potholes for the uninitiated.

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Investor Information Document (KIID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 15 avenue J.F. Kennedy, L-1855 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any. The KIID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A. has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus.

The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer.

This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.