Counting digits

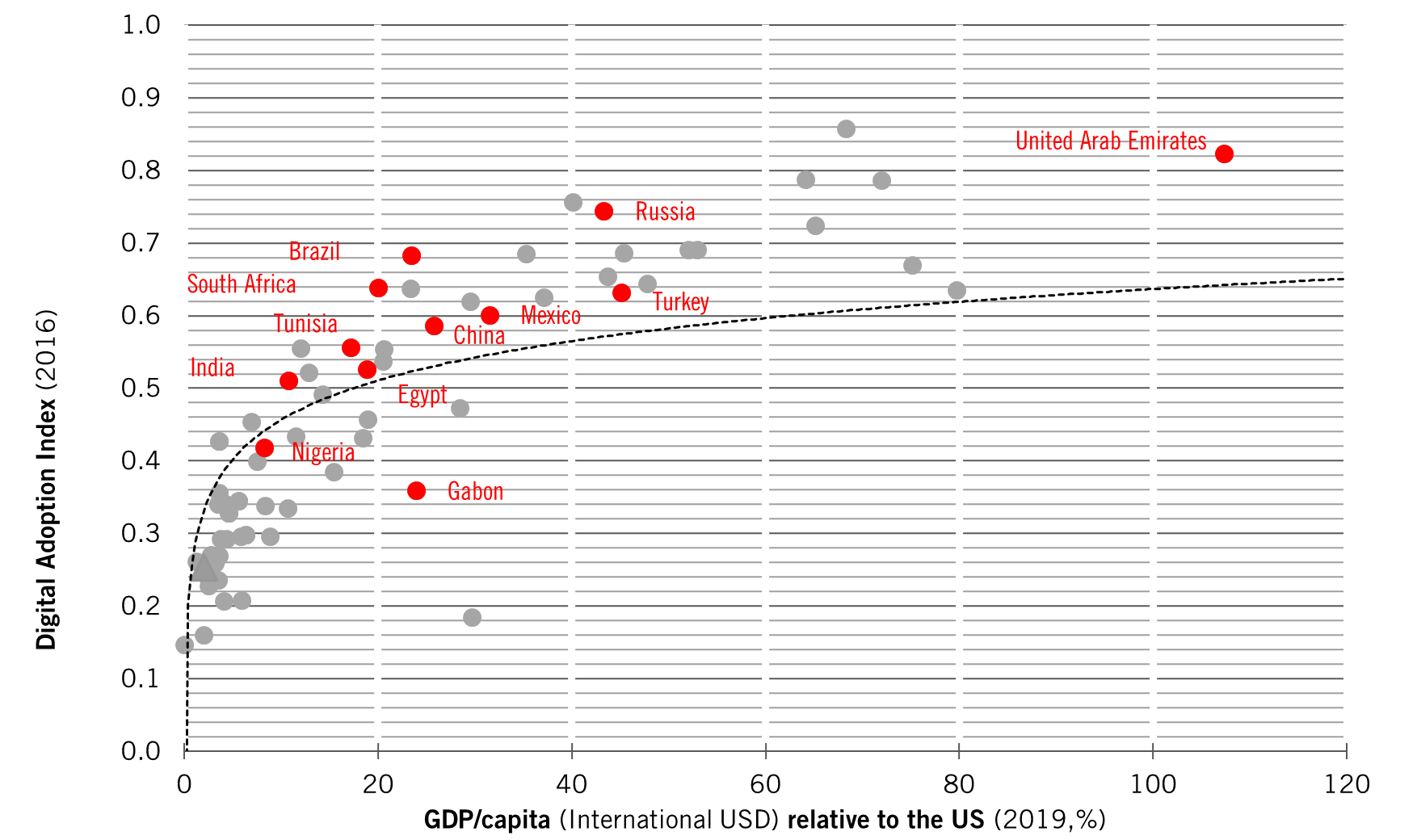

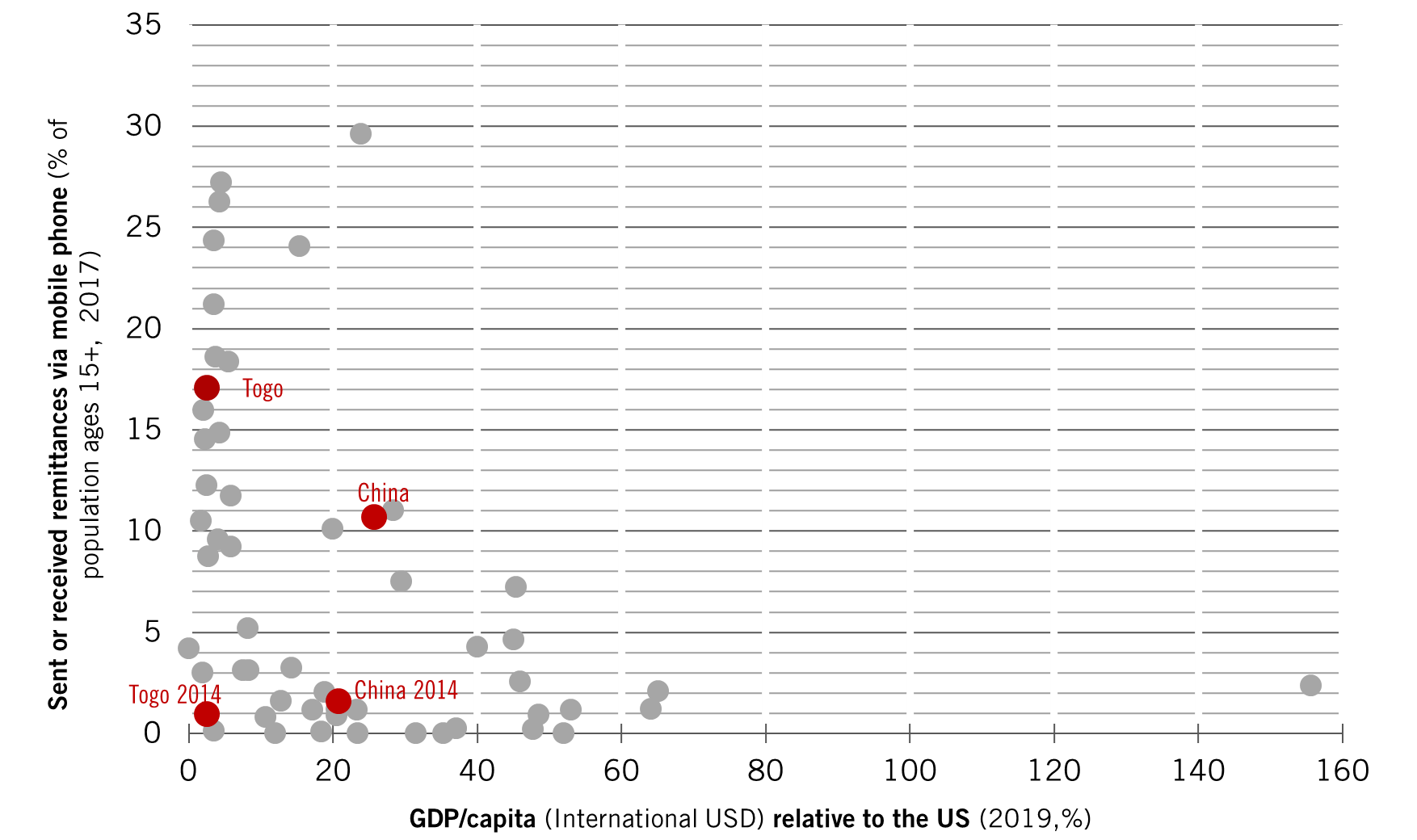

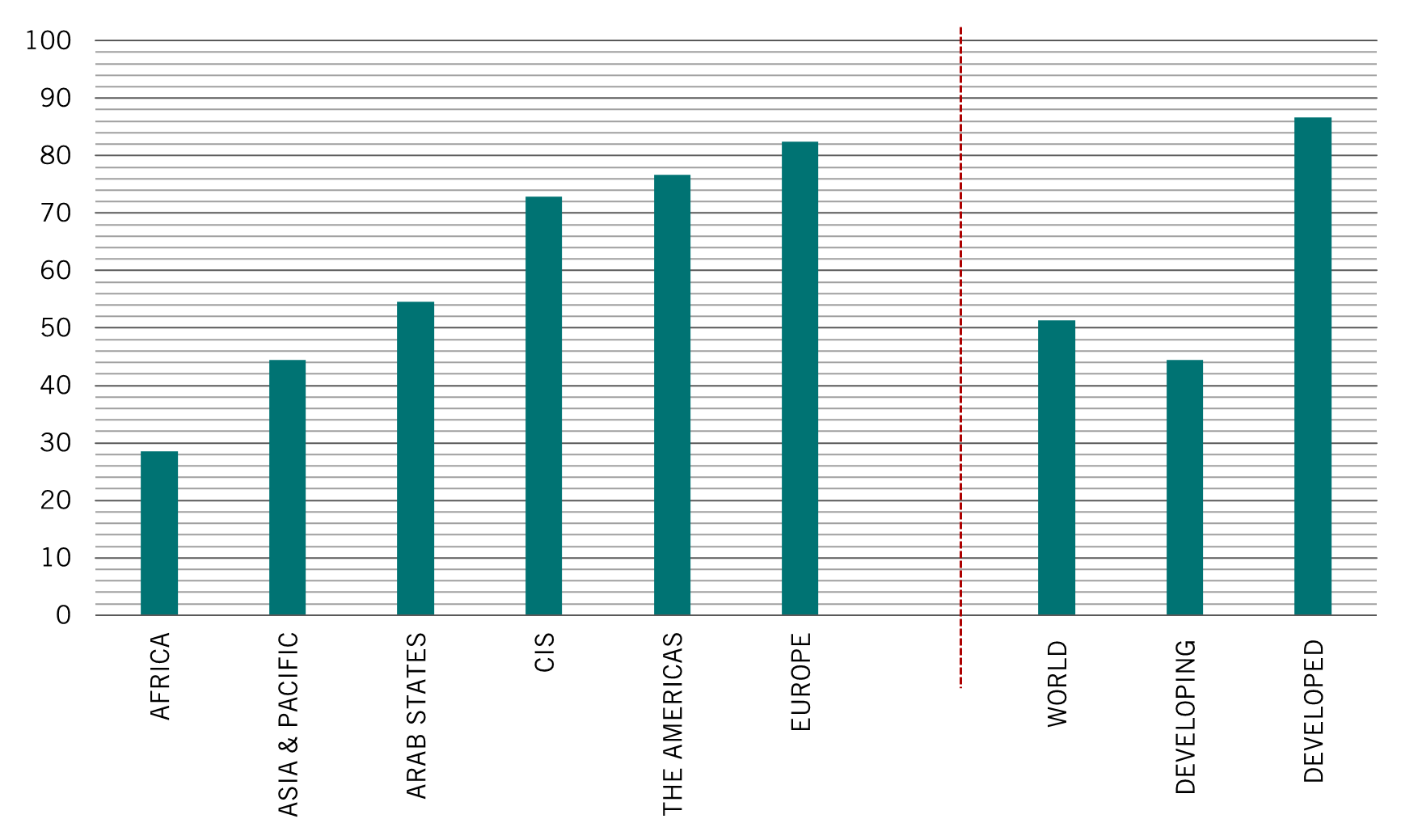

Major economies developed during the 20th century thanks to vast and expensive networks of telecoms or electricity cables. Emerging countries are already compressing decades of this sort of investment into mere years thanks to efficient and relatively cheap mobile telecommunications and small-scale locally generated and sustainable power sources. These, in turn, open up unprecedented economic efficiencies by giving ever greater numbers of people access to information – be it about market prices or how to fix an engine – and services essential to economic growth, not least finance and banking.

Digitalisation is the process of leveraging digital information to improving economic efficiency and business processes. The digital transformation of the past few decades has been on a par with the three previous technological revolutions that each caused a step change in human development: the printing press, the steam engine and electricity generation.

Digitalisation has seen the acceleration of technological adoption. It’s easy to forget how long it took technologies we take for granted to become prevalent, even in the world's leading economy. For instance, in 1915, just 10 per cent of Americans had access to a car. The proportion only hit 90 per cent in 1989. For electric power, an equivalent take-up took 40 years. For household landlines it took 66 years. By contrast, an equivalent shift in mobile phone penetration took just 22 years and only just slightly longer for computer to become similarly prevalent.1

Some of this jump is thanks to the extraordinary leaps in technological complexity and simultaneous drops in prices. Moore’s law – which says microchip transistor capacity doubles every two years – means that in 1971 the most advanced chip had little more than 2000 transistors but by 2020 the count had hit some 50 billion. This, in turn, led to vast increases in computing power. In 1993, the world’s leading supercomputer could do 123 billion operations per second. By 2021 that number had hit 442,000 trillion. Meanwhile, the cost of technology collapsed. So, for instance in the US the price of an equivalent television fell 96 per cent in the twenty years to 2017.2