Bank turmoil will shake economy but won't prompt a re-run of 2008

The state-orchestrated takeover of Credit Suisse and the problems afflicting US regional banks will undoubtedly have economic repercussions. But the chances of a severe credit squeeze are remote.

Cheap money clouds human judgement. It turns meticulous bean-counters into intrepid risk takers and lures ordinarily scrupulous corporations towards endeavours they’d normally recoil from.

It is only when interest rates rise abruptly that the cost of losing one’s bearings is laid bare.

From this vantage point, the collapse of a clutch of regional lenders in the US and the state-orchestrated takeover of Credit Suisse appear as inevitabilities rather than aberrations.

Everybody knows that when central banks tighten the monetary reins, an economic reckoning looms.

Still, it would be mistaken to expect a re-run of the 2008 financial crisis. Economic growth will slow, possibly sharply. Yet the chances of a credit crunch look remote.

One development that should encourage investors is that the regulations introduced in the wake of US bank Lehman Brothers’ collapse more than a decade ago have greatly strengthened the foundations on which global banking rests.

Bad loans – the root cause of the 2008 crisis - will always be a problem when rates rise. But they no longer plague bank balance sheets as they once did.

In Europe, in response to more stringent capital requirements, banks have reduced bad loans from some EUR1 trillion 10 years ago to under EUR350 billion, equivalent to less than 2 per cent of total lending. Banks looks healthy on other measures, too.

Data from the European Banking Authority show that banks’ liquidity coverage ratios – the amount of highly liquid assets banks hold relative to the deposit withdrawals they can expect over a 30-day period - are running at an average of 162 per cent across the region. That compares with a mandatory level of 100 per cent.

Loan to deposit ratios among US banks, meanwhile, have fallen to 70 per cent in aggregate from around 95 per cent in 2007-2008, data from Barclays shows.

Stronger bank balance sheets are not the only positive legacy from 2008. The policy framework underpinning the global banking industry is also much improved.

Bruised by the experience of the sub-prime mortgage crisis, central banks have evolved into astute stewards of the financial system. Led by the US Federal Reserve, which was early to recognise the limits of conventional monetary policy in containing financial risk, the world’s major central banks have developed an impressively wide range of anti-crisis tools.

Quantitative easing, forward guidance and subsidised loans to banks - most recently in the shape of the Fed's USD300 billion Bank Term Lending Program - have been deployed alongside purchases of corporate loans, bonds and equities.

Working in tandem with national governments, there is arguably no limit to what central banks can do to safeguard the financial system. If Lehman Brothers' collapse was policymakers’ darkest hour, the takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS should cast them in a much more favourable light.

None of this is to say the economy will emerge unscathed.

Consumer and business sentiment will inevitably suffer in the wake of the banking sector’s convulsions. Bank lending could also slow appreciably.

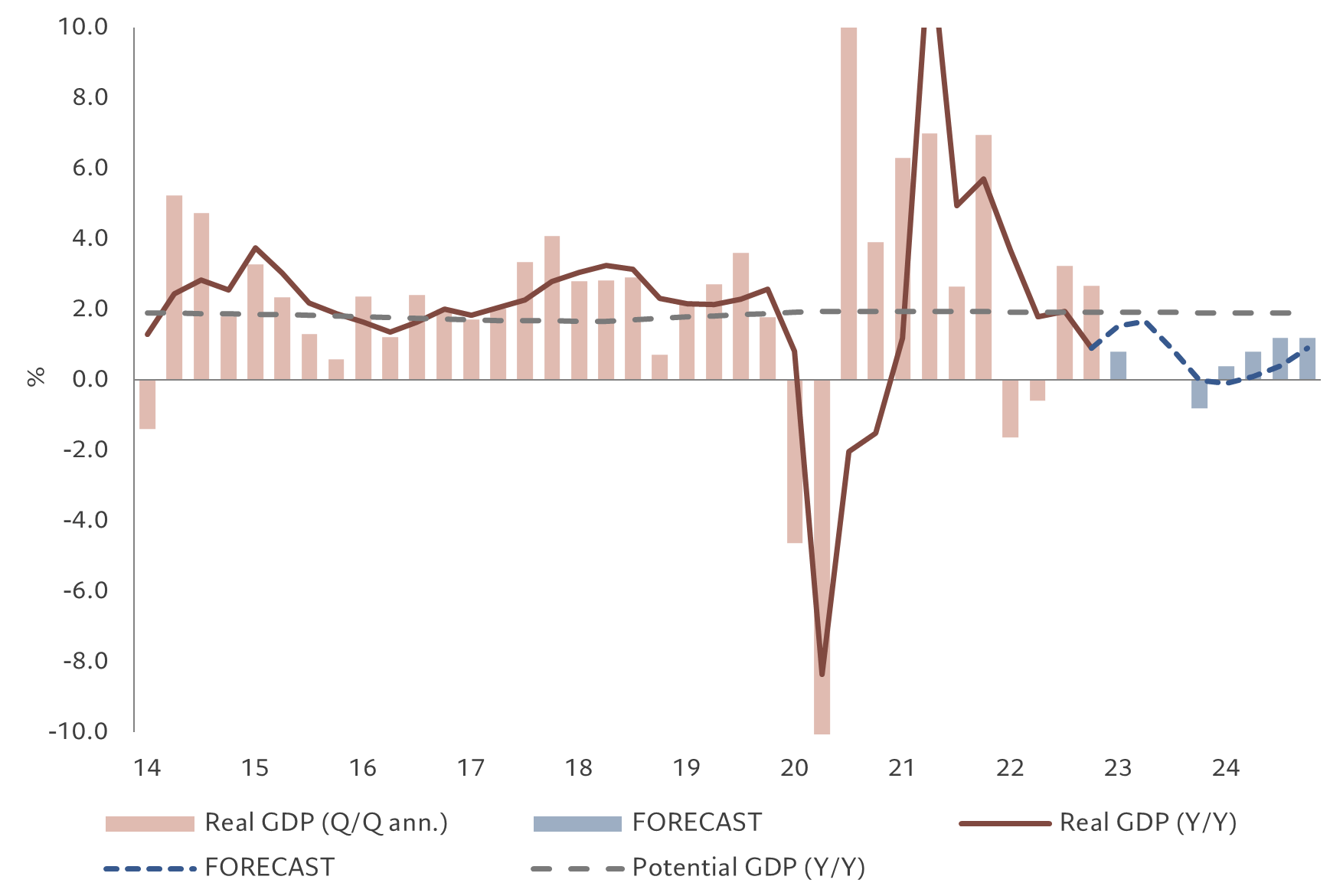

For these reasons, we have cut our GDP growth forecasts for the global economy this year; we now see the US economy flatlining year-on-year by the fourth quarter of 2023 compared to an earlier forecast of 0.4 per cent growth.

One economic risk emerging from Credit Suisse’s takeover is the possible demise of the Additional Tier 1 (AT1) bond market, a source of funding that banks worldwide have come to rely on. Its future has been thrown into doubt after holders of AT1 bonds issued by Credit Suisse unexpectedly saw their investments wiped out as part of the UBS acquisition. These securities were introduced in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008 to prevent taxpayer-funded bailouts of the banking sector.

The bonds paid investors high coupons because they carried the risk of being converted into equity in the event of a financial restructuring. With interest rates at rock-bottom levels, AT1 securities proved popular with investors and banks alike, and the market grew to almost USD300 billion. But the wipe-out of Credit Suisse AT1 bonds could have damaging consequences. At the very least, it could motivate investors to demand higher coupons on such debt and thereby increase bank funding costs. This, in turn, could depress lending, which would exacerbate an existing trend, particularly among smaller and mid-sized US banks. Any further retrenchment here is likely to squeeze the supply of credit to the small businesses and households that tend to rely on local banks. This could have serious economic repercussions.

The banking sector’s woes could also affect sentiment among consumers and companies. Should confidence suffer, there is a fair chance it will weigh on consumption spending and business investment, with both households and corporations more likely to hold on to the savings accumulated during the pandemic.

Some investment banks – such as JP Morgan – have warned that recent banking troubles could cut GDP growth by as much as 1 percentage point over the coming two years. In our view, the economy should prove a little more resilient, not least because the Fed is likely to respond to the financial squeeze by reducing the ultimate peak of rates in this cycle.

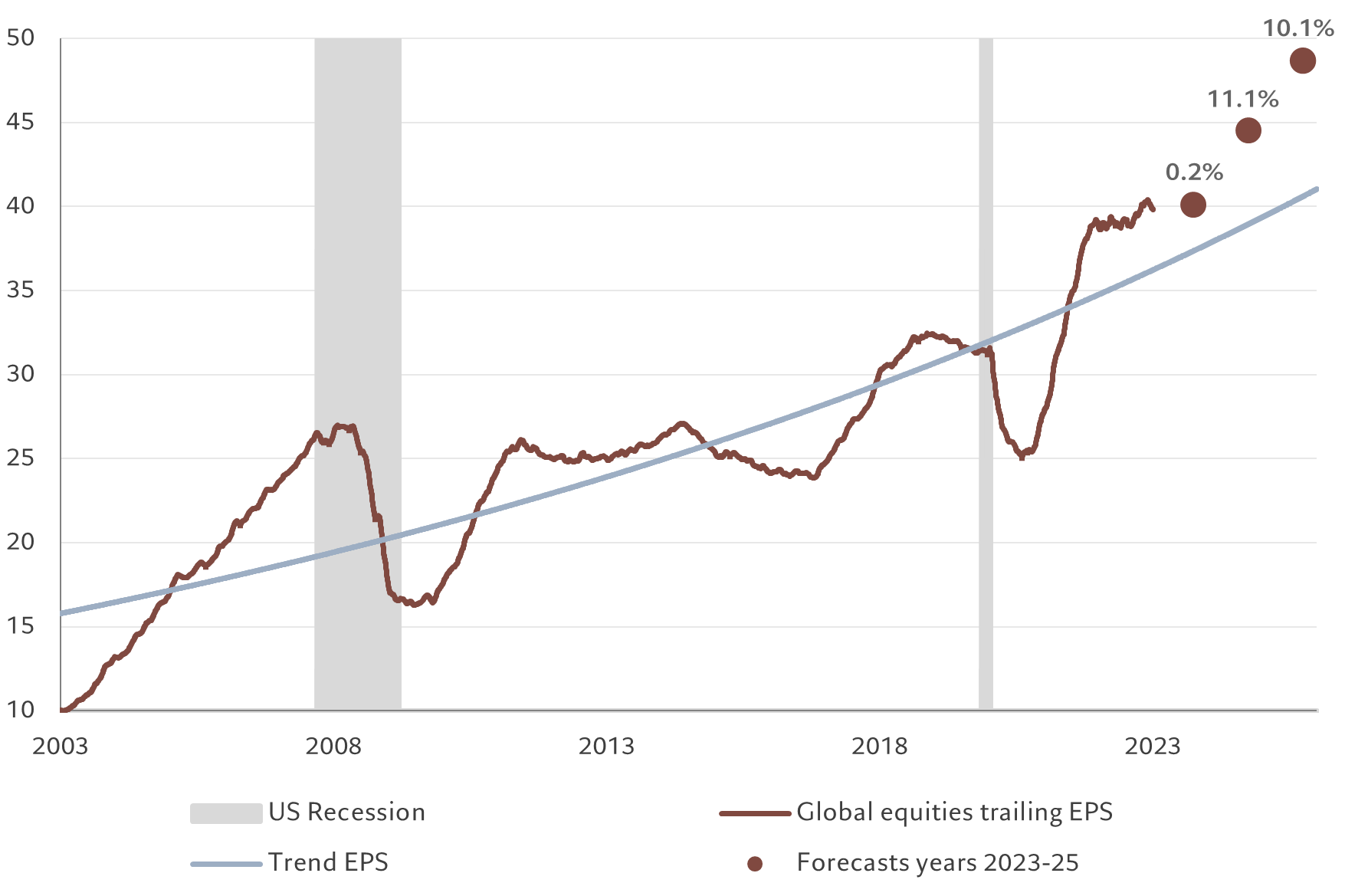

But this is certainly an economic headwind that could buffet financial markets over the near term. For their part, investors should prepare for a change in market dynamics.

Small cap stocks and cyclical equities look particularly vulnerable to a further correction, as do riskier bonds such as high yield debt. None of these asset classes sufficiently discount the probability of a further deterioration in economic conditions. By contrast quality stocks – companies with stable revenues that are less sensitive to swings in the business cycle – should hold up well. Government bonds could also rally. Markets, then, are about to see more upheaval as the economic weather worsens. But the banking turmoil currently unfolding in the US and Europe should not lead to severe financial distress.

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.